Results from 541 to 600 of 1138

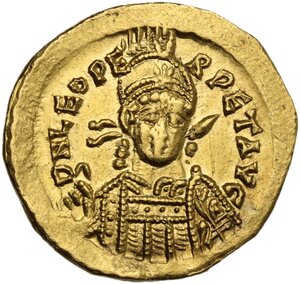

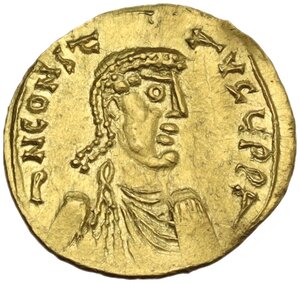

Constans' Solidus

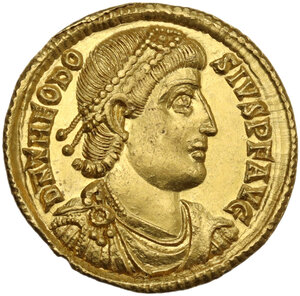

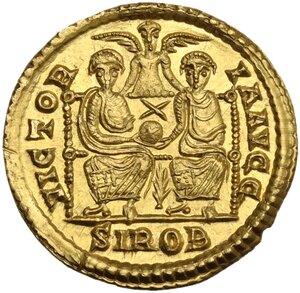

Uncirculated Theodosius I Solidus

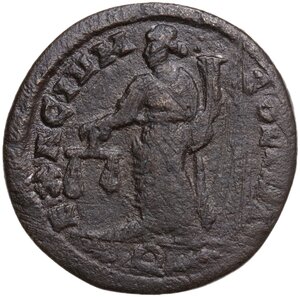

Unmodified Exagium Solidi

Ravenna mint Honorius' Tremissis

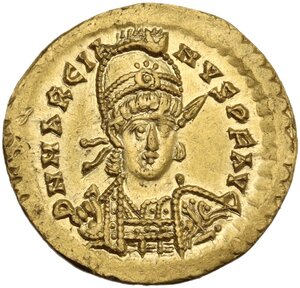

Extremely Rare Constantius III Solidus

Charming Majorianus

Rome Mint Anthemius Solidus

The Last Roman "Sestertius".

Exceptional 250 Nummi

Outstandig Ravenna Mint Follis

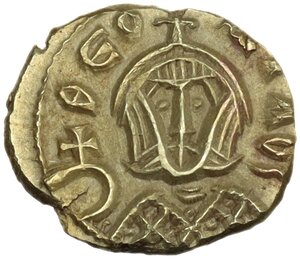

Less than Ten Known

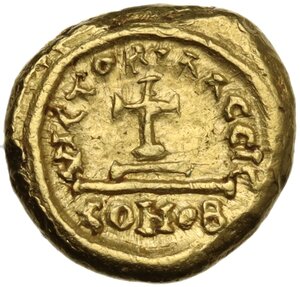

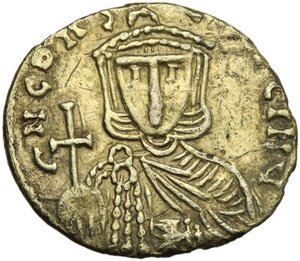

Artavasdus Second Known Tremissis

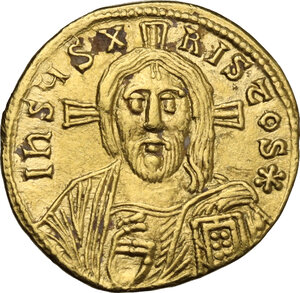

Choice Theophilus

Results from 541 to 600 of 1138