Results from 1 to 23 of 23

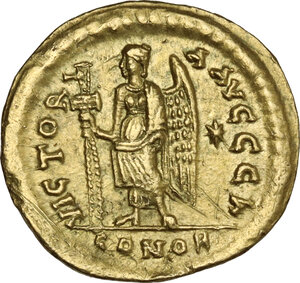

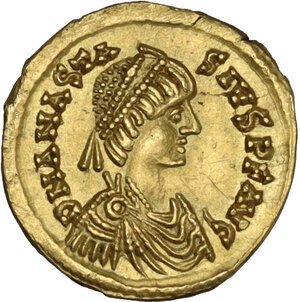

Athalaric Solidus

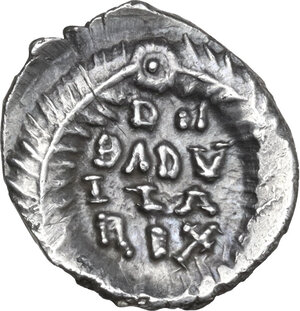

Athalaric Solidus

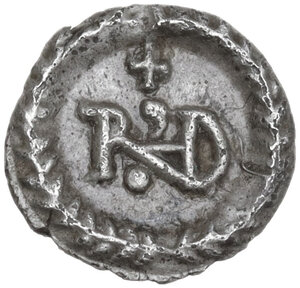

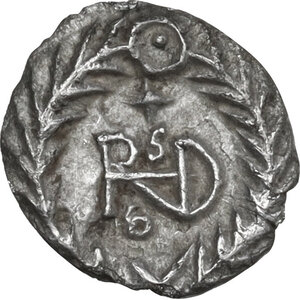

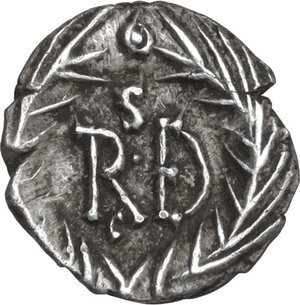

Amalasuntha Quarter Siliqua

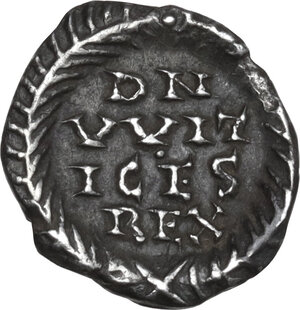

Witigis Solidus

Visigoth Tremissis

Superb Sisebut

Amazing Lombardic Tremissis

Results from 1 to 23 of 23