Results from 421 to 480 of 1218

The Gallic Chieftain Vercingetorix

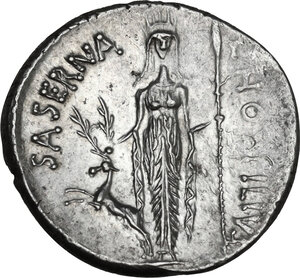

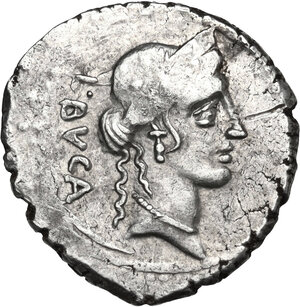

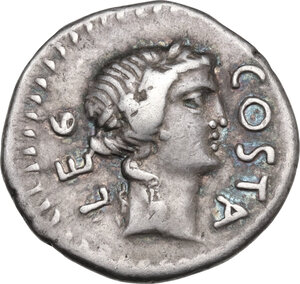

Superb Sad Gallia

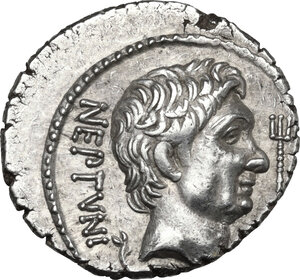

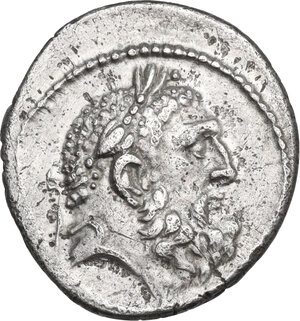

Impressive Pan

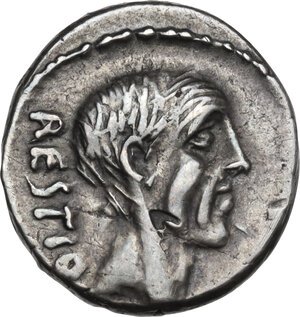

Realistic Antius Restio portrait,

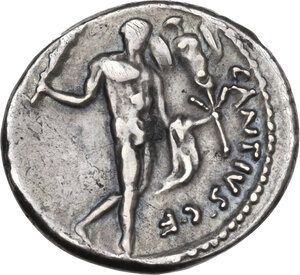

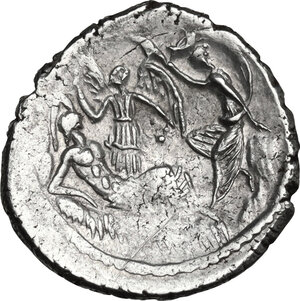

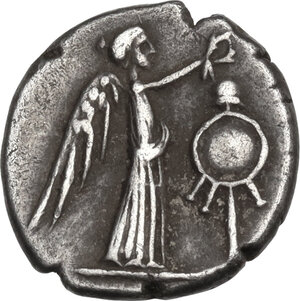

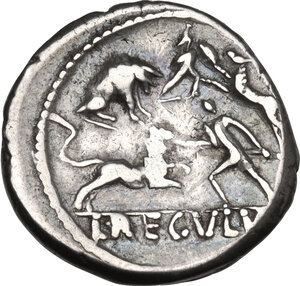

Aeneas and Anchises escape from Troy

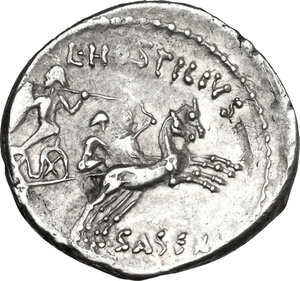

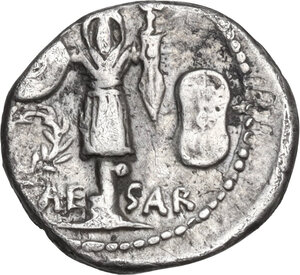

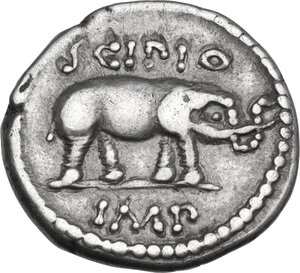

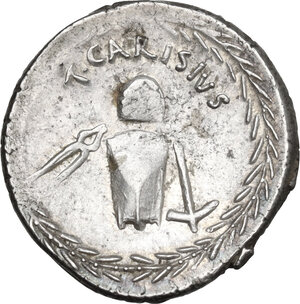

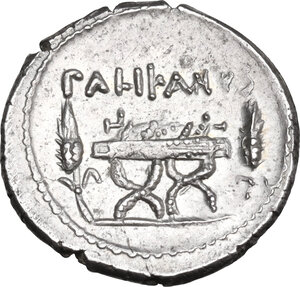

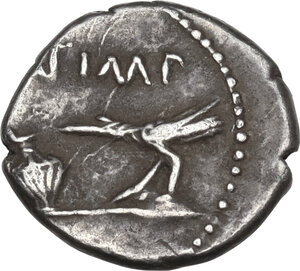

Tools for Striking Coinage

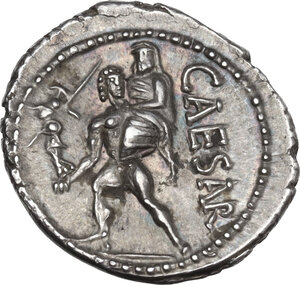

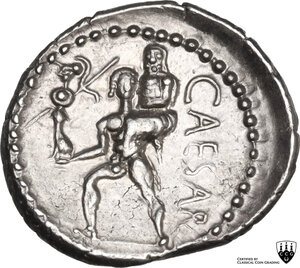

The aureus distributed during Caesar's triumph of October 45 BC

Sulla's Dream

Exceptional Smiling Caesar

Exceptional Provincial Julius Caesar's Portrait

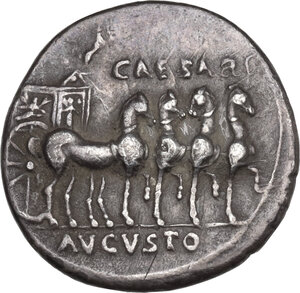

The Capitoline Temple of Jupiter.

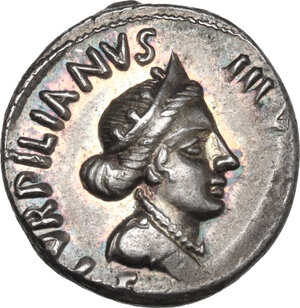

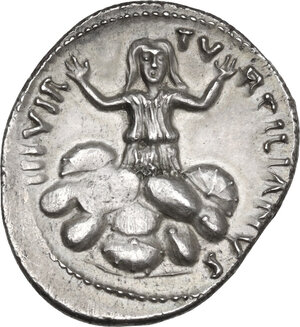

Exceptional Clodius Turrinus

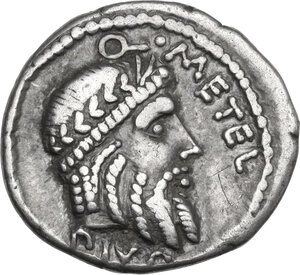

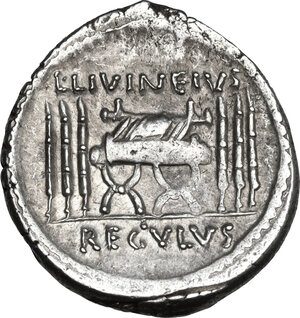

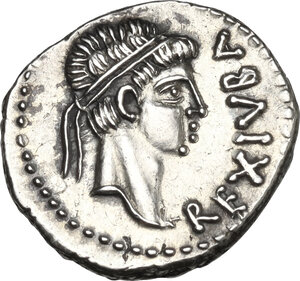

Outstanding Regulus' Portrait

Impressive Hercules

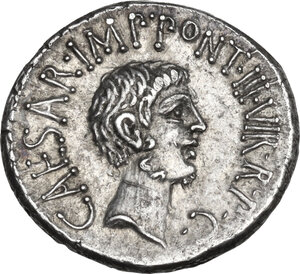

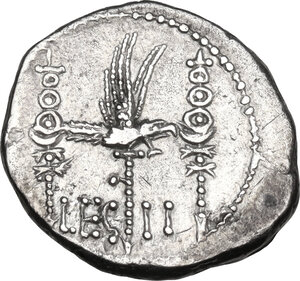

Two Excellent Triumvirs Portraits

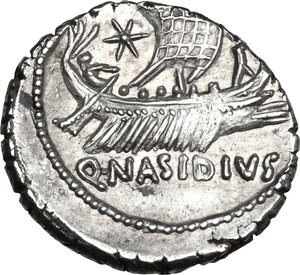

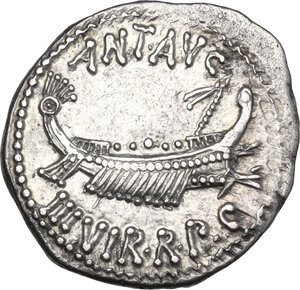

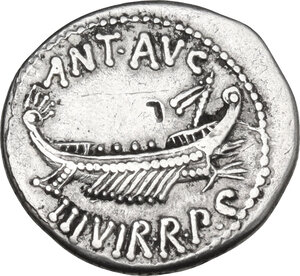

Spectacular Galley

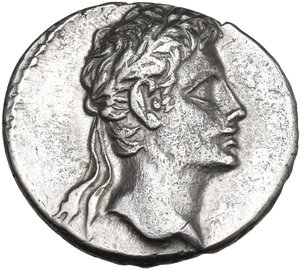

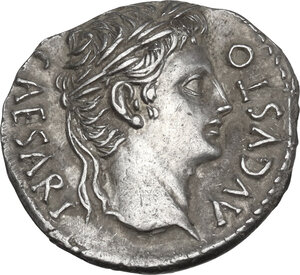

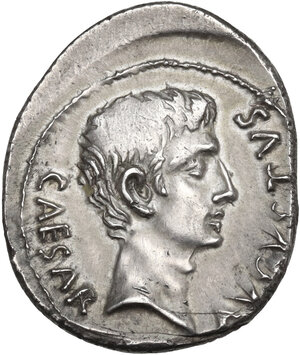

A charming portrait of Augustus

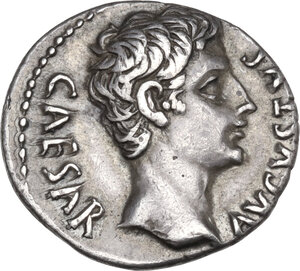

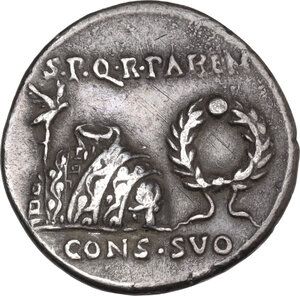

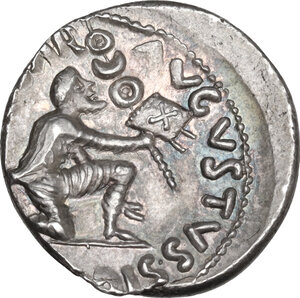

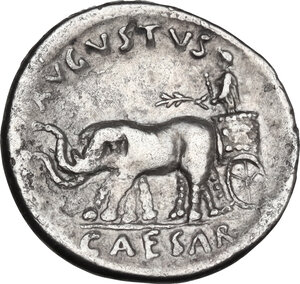

Return of the Standards Lost by Crassus

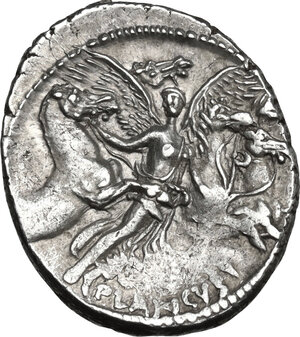

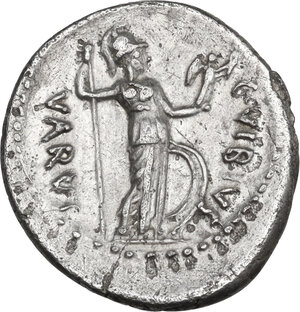

Enchanting Tarpeia

Superb Augustus' Dupondius

Outstanding Nero Claudius Drusus Portrait

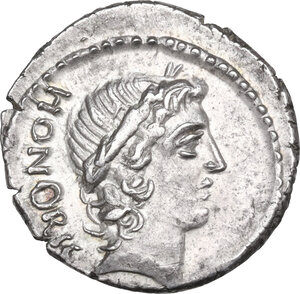

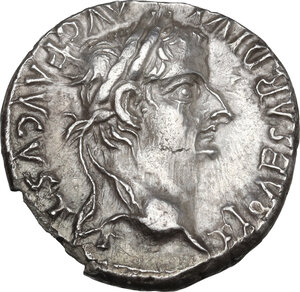

Bold Portrait

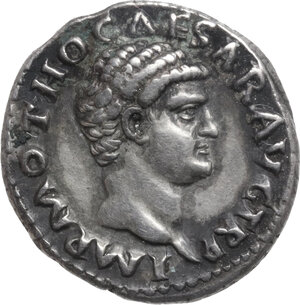

Otho Denarius

Results from 421 to 480 of 1218