Results from 421 to 480 of 1305

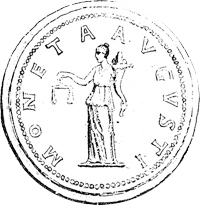

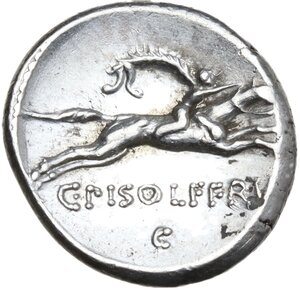

Piso Frugi Quadrans

A Spectacular Mis-strike

Masterpiece in Miniature

Hitherto Unknown

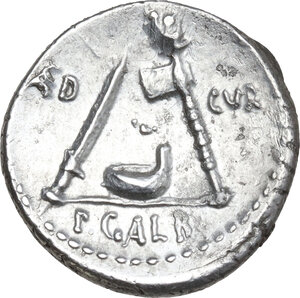

Unpublished C. Censorinus Quadrans

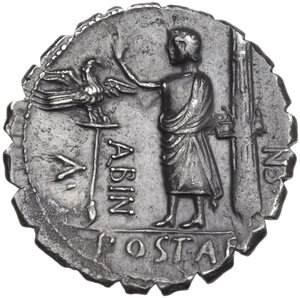

Ulysses and Argus

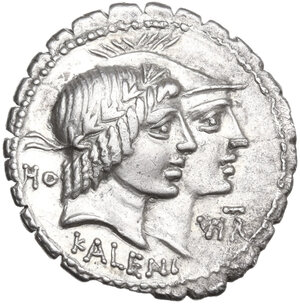

The only Perenna's Portrait from Ancient World.

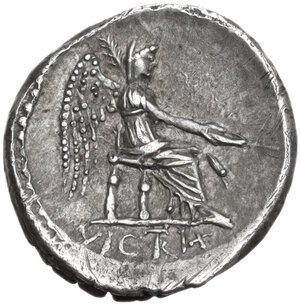

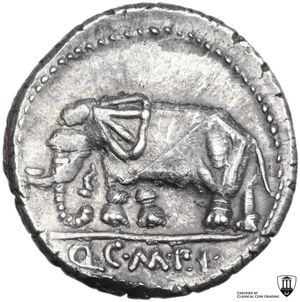

Enchanting Q.C.M.P.I. Denarius

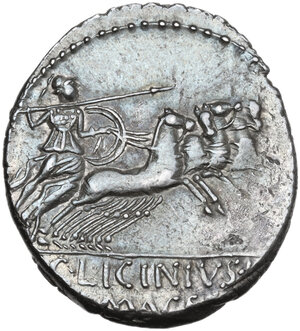

Exceptional Naevius Balbus

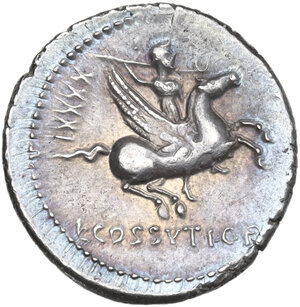

Medusa and Bellerophon.

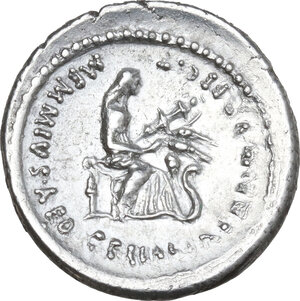

Enchanting Sors

Amazing Cr. 405/3b

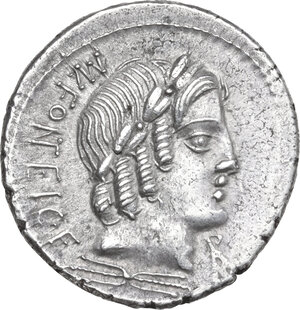

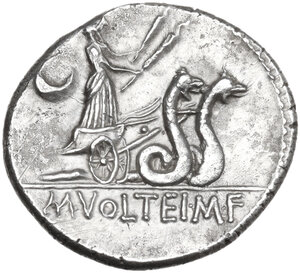

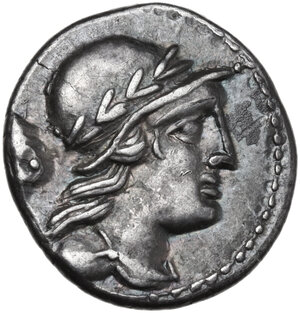

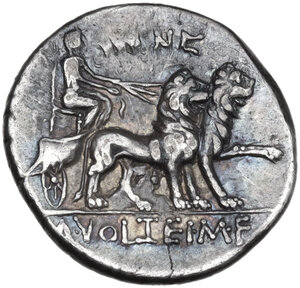

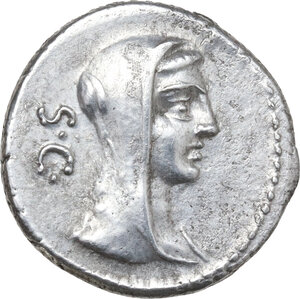

Delightful Vesta

No Spear Cr. 407/2

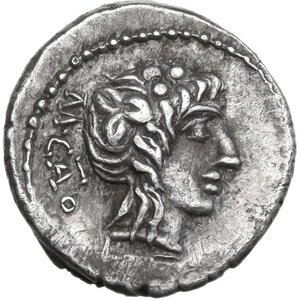

Centred Piso Frugi Denarius

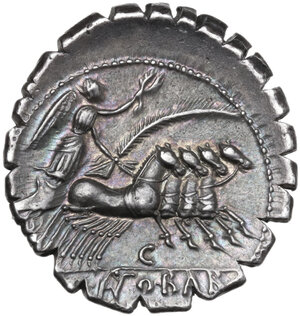

Spectacular Plaetorius Cestianus

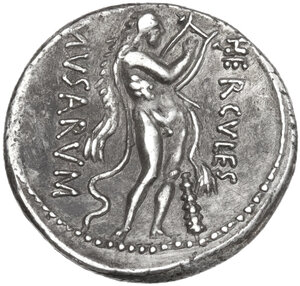

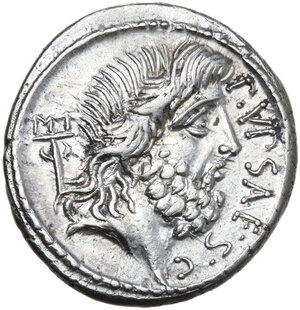

Hercules Musagetes

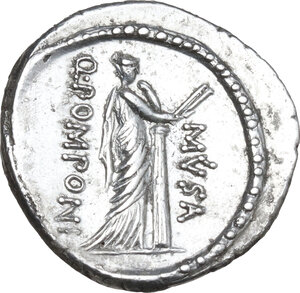

Charming Euterpe

Not Intended Erato

Centred Urania

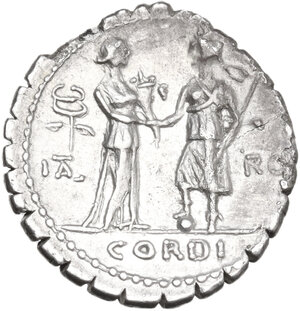

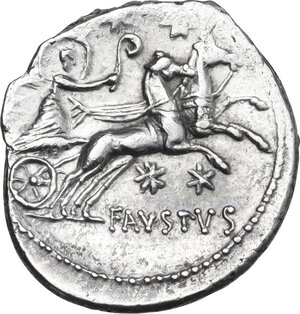

The Submission of Perseus

Alexandria's Depiction

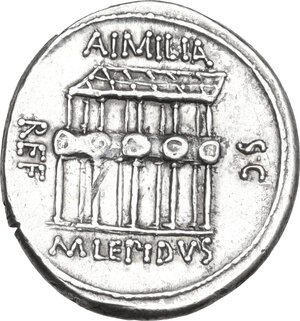

The Basilica Aemilia

Choice Plautius Hypsaeus

Choice Plautius Hypsaeus

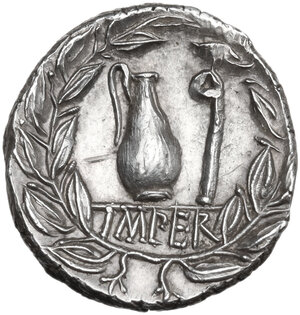

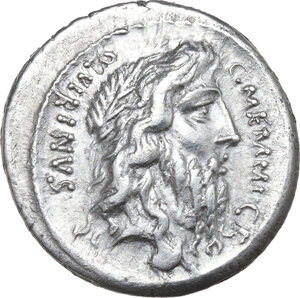

Rare Sulla Denarius

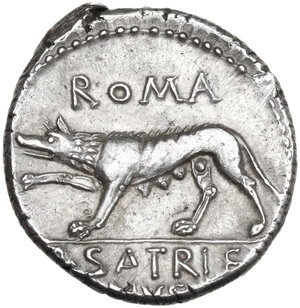

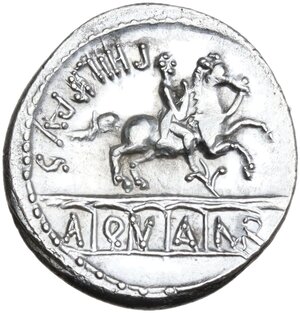

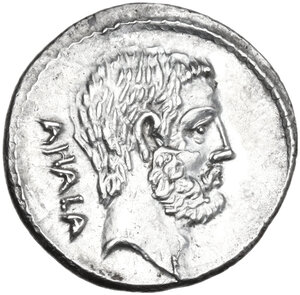

Impressive Romulus Quirinus

The Villa Publica

Enchanting Valetudo

From Este Collection (?)

Results from 421 to 480 of 1305