Results from 721 to 780 of 1305

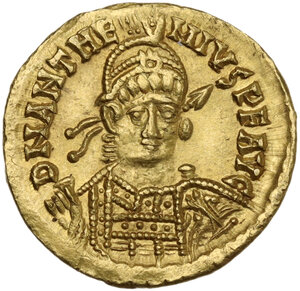

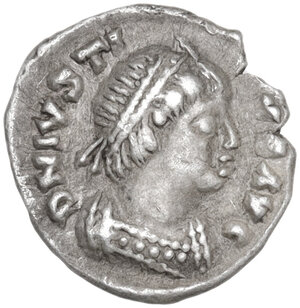

Odovacar Tremissis

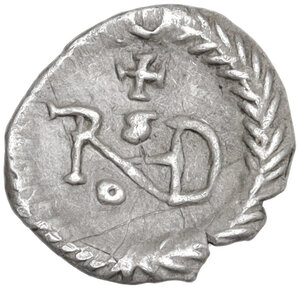

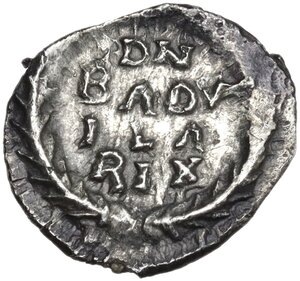

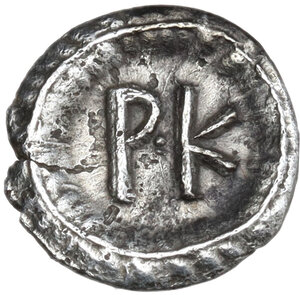

Amalasuntha Quarter Siliqua

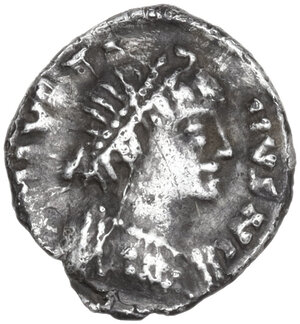

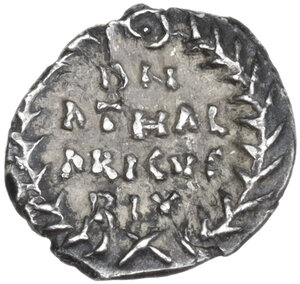

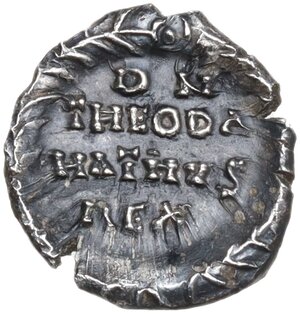

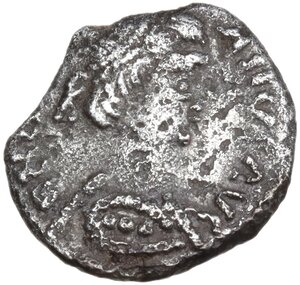

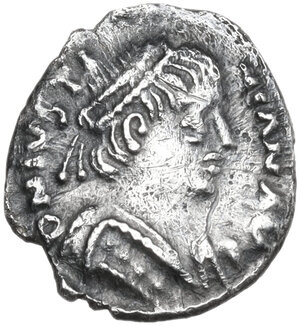

Extremely rare Theia

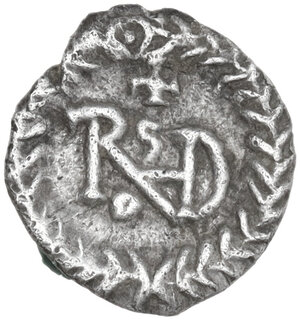

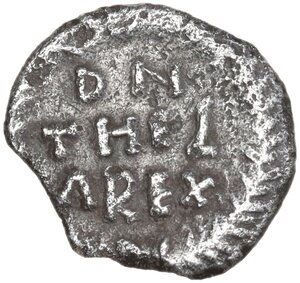

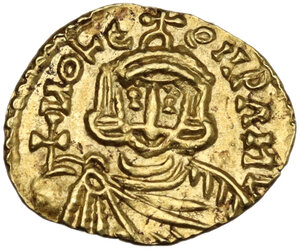

Amazing Lombardic Tremissis.

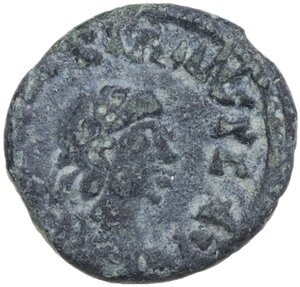

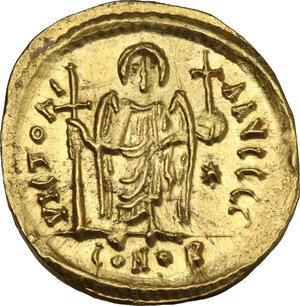

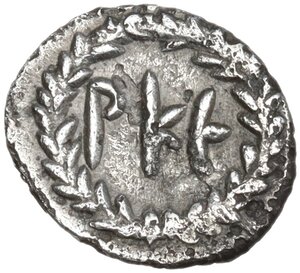

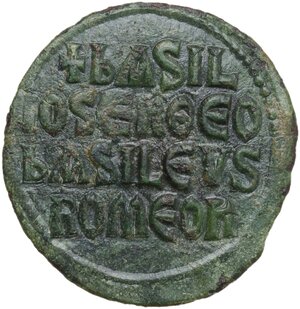

Aistulf unpublished AE

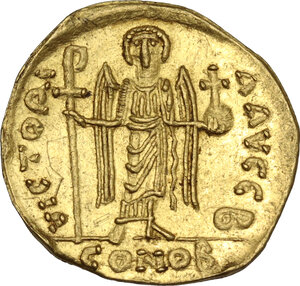

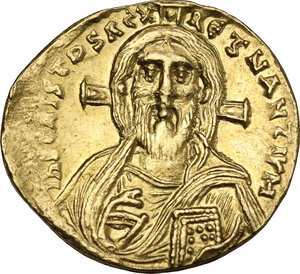

Outstanding Tremissis

Amazing Tremissis

Catlike Irene

Exciting Simeon The Great's Seal

Results from 721 to 780 of 1305