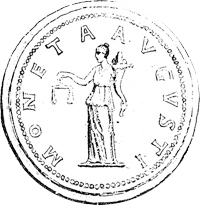

Ostrogothic Italy. Non-Regal Bronze Issue from the Period of Theoderic and Athalaric. AE Double Follis. Early to mid 6th century. 'Countermarked' early Imperial bronze issue. LXXXIII (mark of value = 83 Nummi) cut into obverse of AE Sestertius of Galba (Rome mint, 68-69 AD). Obv. [SER GALBA] IMP CAES AVG TR P. Laureate head right. Rev. AVGVSTA, S-C. Livia seated right, holding patera and sceptre. Cf. MEC 1, 65; For undertype: Galba RIC I (2nd ed.), 335. 22.33 g. 35.00 mm. RRR. Extremely rare and fascinating. Lovely dark patina with minor earthy deposits. VF. These countermarked issues have long been considered as made in Vandalic North Africa, but the hoard evidence and the results of the latest studies makes it seem that they were, in fact, made in the Ostrogothic Italy, and were in use there during the first quarter or first half of the 6th century (Cf, NAC, May 1993, 457).

These countermarked issues have long been considered as made in Vandalic North Africa, but the hoard evidence and the results of the latest studies makes it seem that they were, in fact, made in the Ostrogothic Italy, and were in use there during the first quarter or first half of the 6th century (Cf, NAC, May 1993, 457).

The mark of value XLII refers to a twelfth of a silver unit valued at 500 nummi, which itself amounts to the 24th

fraction of a gold solidus valued at 12,000 nummi. (Cf. Grierson, MEC, p.28-31).

These are not countermarked coins in the usual sense of word, since the LXII figure was not punched or stamped with a single instrument, but seems to have been cut or incised with several chisel strokes. (C. Morrisson,1983).

J. Friedlander suggested that for the more finely incised series the pieces were certainly softened by fire in order to be able to engrave more easily the deep and crude strokes. (“Die Erwerbungen des Konigl. Munzkabinets vom 1.Jan.1877 bis 31 Marz 1878” ZfN VI, 1879, p.1-26).

Such crude workmanship seems to point to the markings being done by private persons, at least in the case of the most anomalous countermarks. While for the more finely incised countermarks – like our outstanding example – the role of some official authority cannot be excluded. (C. Morrisson).

Tentatively, Morrisson suggests that an official practice of marking and re-issuing older bronzes was followed with varying success by private individuals as and when they came into possession of similar pieces. (Morrisson, C. “The re-use of obsolete coins : the case of Roman imperial bronzes revived in the late fifth century” in: ed. C.N.L.

Brooke et al. Studies in Numismatic Method presented to Philip Grierson, Cambridge 1983.XLVI, 487).

For completeness of information, two more recent studies are also reported which specifically dealt with the problem of coins with these rebated numerals:

Asolati M. "I bronzi Imperiali contromarcati con numerali lXXXIII e XlII: nuove ipotesi interpretative" in: Praestantia nummorum. Temi e note di numismatica tardo antica e alto medievale, Padova 2012, Numismatica Patavina, 11 and Asolati M. "Nuove scoperte sulle monete bronzee d’età imperiale con contromarche XLII e LXXXIII", in Percorsi nel passato. Miscellanea di studi per i 35 anni del Gr.A.V.O. e i 25 anni della Fondazione Colluto, a cura di A. VIGONI, Rubano (PD) 2018 (L’Album 22), pp. 253-265.

These countermarked issues have long been considered as made in Vandalic North Africa, but the hoard evidence and the results of the latest studies makes it seem that they were, in fact, made in the Ostrogothic Italy, and were in use there during the first quarter or first half of the 6th century (Cf, NAC, May 1993, 457).

The mark of value XLII refers to a twelfth of a silver unit valued at 500 nummi, which itself amounts to the 24th

fraction of a gold solidus valued at 12,000 nummi. (Cf. Grierson, MEC, p.28-31).

These are not countermarked coins in the usual sense of word, since the LXII figure was not punched or stamped with a single instrument, but seems to have been cut or incised with several chisel strokes. (C. Morrisson,1983).

J. Friedlander suggested that for the more finely incised series the pieces were certainly softened by fire in order to be able to engrave more easily the deep and crude strokes. (“Die Erwerbungen des Konigl. Munzkabinets vom 1.Jan.1877 bis 31 Marz 1878” ZfN VI, 1879, p.1-26).

Such crude workmanship seems to point to the markings being done by private persons, at least in the case of the most anomalous countermarks. While for the more finely incised countermarks – like our outstanding example – the role of some official authority cannot be excluded. (C. Morrisson).

Tentatively, Morrisson suggests that an official practice of marking and re-issuing older bronzes was followed with varying success by private individuals as and when they came into possession of similar pieces. (Morrisson, C. “The re-use of obsolete coins : the case of Roman imperial bronzes revived in the late fifth century” in: ed. C.N.L.

Brooke et al. Studies in Numismatic Method presented to Philip Grierson, Cambridge 1983.XLVI, 487).

For completeness of information, two more recent studies are also reported which specifically dealt with the problem of coins with these rebated numerals:

Asolati M. "I bronzi Imperiali contromarcati con numerali lXXXIII e XlII: nuove ipotesi interpretative" in: Praestantia nummorum. Temi e note di numismatica tardo antica e alto medievale, Padova 2012, Numismatica Patavina, 11 and Asolati M. "Nuove scoperte sulle monete bronzee d’età imperiale con contromarche XLII e LXXXIII", in Percorsi nel passato. Miscellanea di studi per i 35 anni del Gr.A.V.O. e i 25 anni della Fondazione Colluto, a cura di A. VIGONI, Rubano (PD) 2018 (L’Album 22), pp. 253-265.