Results from 121 to 180 of 228

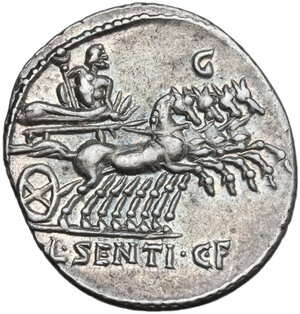

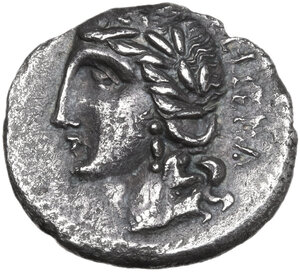

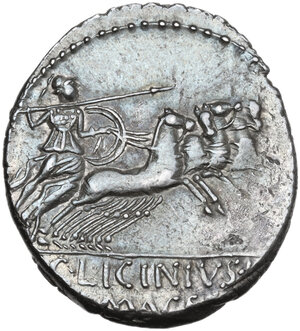

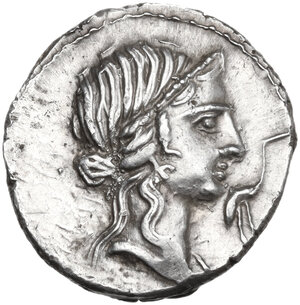

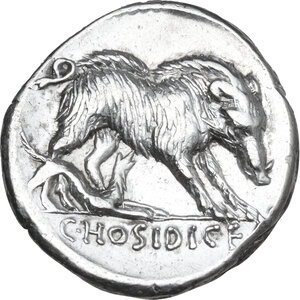

Marius Triumphator

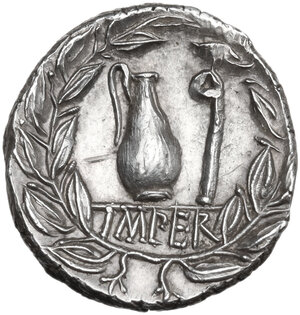

Detailed Reverse Die.

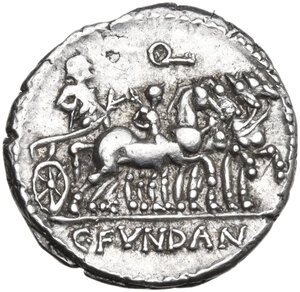

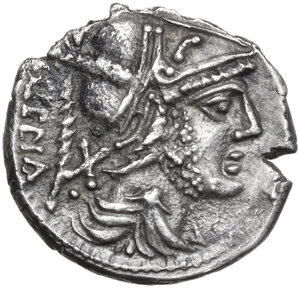

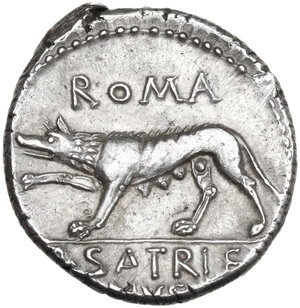

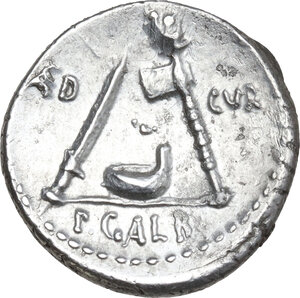

The Marsic Confederation

Extremely Rare Campana 98

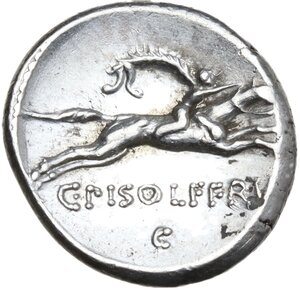

Piso Frugi Quadrans

A Spectacular Mis-strike

Masterpiece in Miniature

Hitherto Unknown

Unpublished C. Censorinus Quadrans

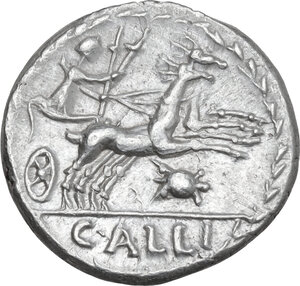

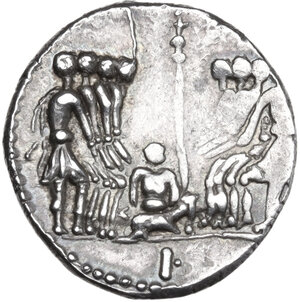

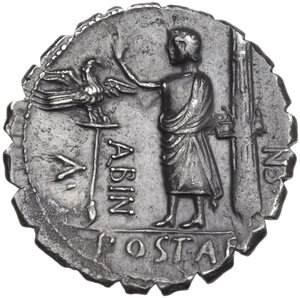

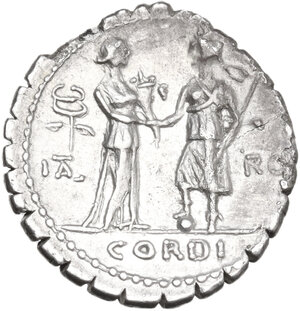

Ulysses and Argus

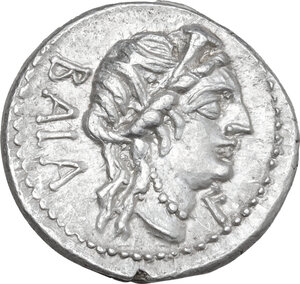

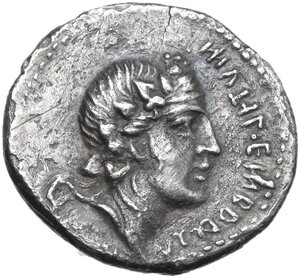

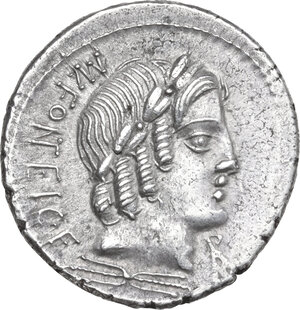

The only Perenna's Portrait from Ancient World.

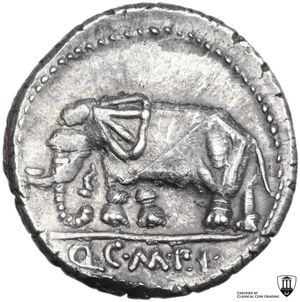

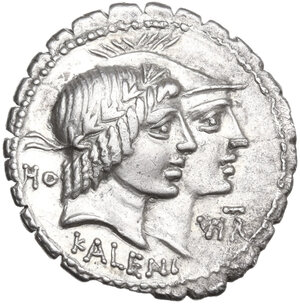

Enchanting Q.C.M.P.I. Denarius

Exceptional Naevius Balbus

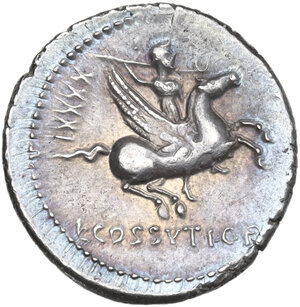

Medusa and Bellerophon.

Enchanting Sors

Amazing Cr. 405/3b

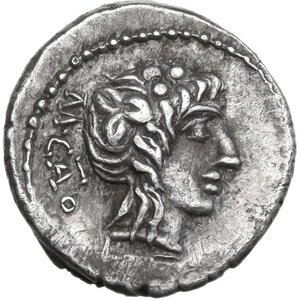

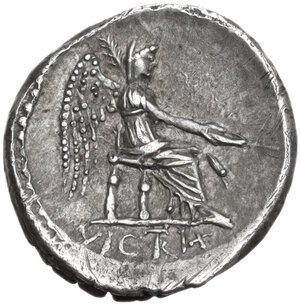

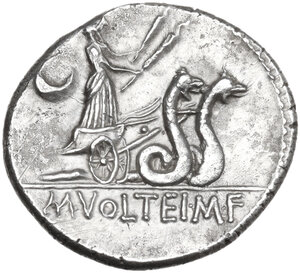

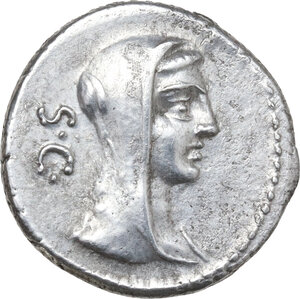

Delightful Vesta

No Spear Cr. 407/2

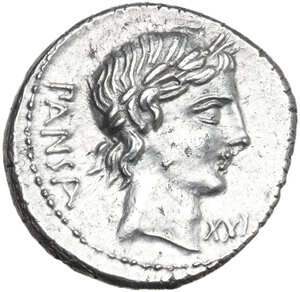

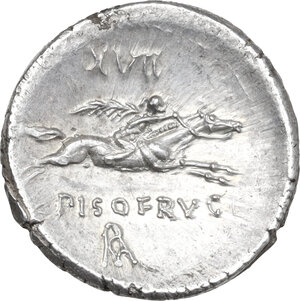

Centred Piso Frugi Denarius

Spectacular Plaetorius Cestianus

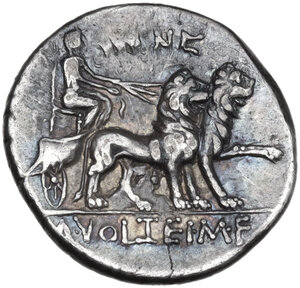

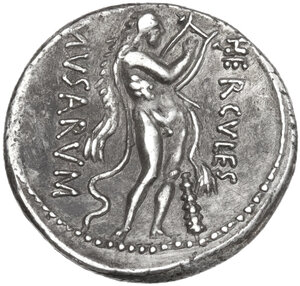

Hercules Musagetes

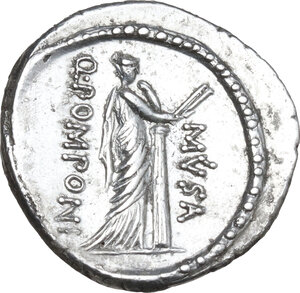

Charming Euterpe

Not Intended Erato

Centred Urania

Results from 121 to 180 of 228