Results from 121 to 180 of 1081

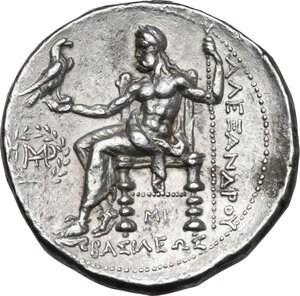

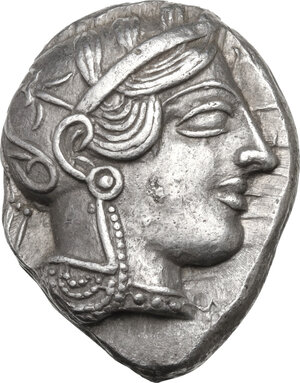

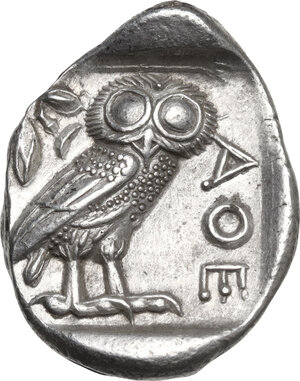

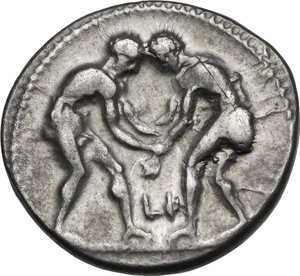

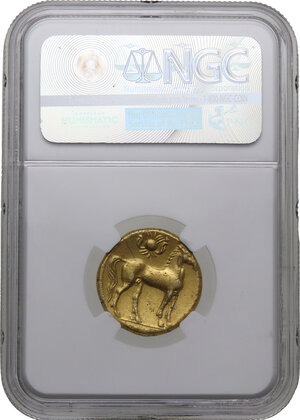

Group IV Tetradrachm

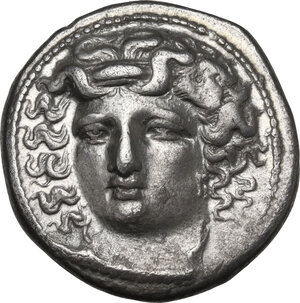

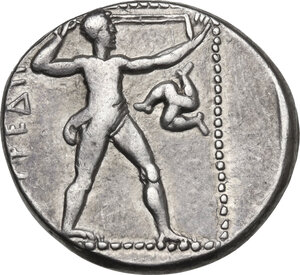

Exceptional Small Head and Full Crest.

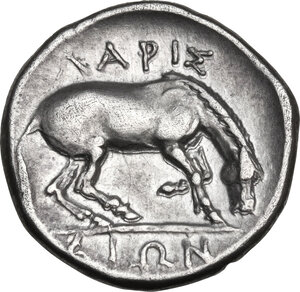

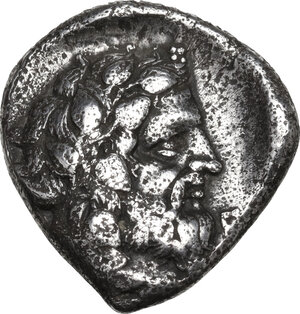

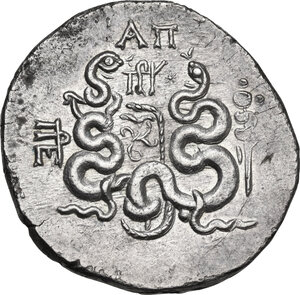

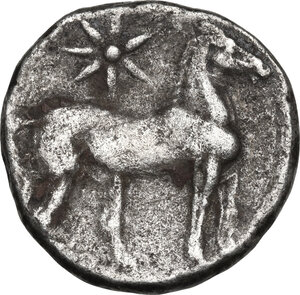

Unpublished Carian Chersonesos Drachm

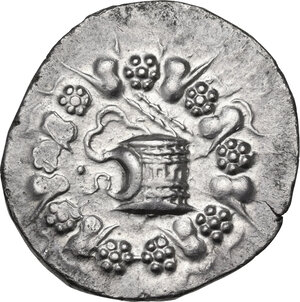

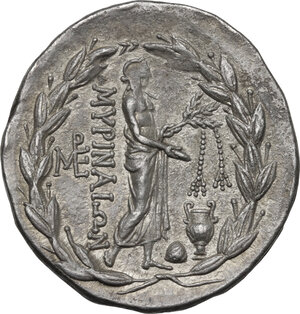

The Juda Iscariot's Price.

Results from 121 to 180 of 1081